Parallel Space Blog #01

Why most innovations of academic researchers in Europe fail to be monetized.

6 min read – Oct 2022 - By Dr. Axel Schumacher

Usually, there are several reasons named why European tech start-ups struggle to catch up with those that come out of Silicon Valley: A lack of access to huge funding rounds or available risk-taking investors, the fact that revenue is prioritized, forcing entrepreneurs to focus more on immediate returns rather than growth of the company, and the manifold problems of a diversified (more fragmented) EU market. However, there is another, less discussed factor that I want to highlight in this article.

A lack of sophisticated start-up platforms at European research institutions.

Remember, most deep-tech start-ups are founded by scientists who are not trained to build companies. However, in Europe, researchers are often less incentivised to spin-off companies or to monetize their IP compared to their US counterparts. Many universities are still lacking proper venture labs, accelerators, platforms, or incubators to support their scientists and students. As such, it is not surprising that the EU start-up ecosystem seems to be quite saturated. For example, while between 2015 and 2020, the number of European tech start-ups soared, we see an opposite trend now: the number of start-ups founded in Germany is declining, and that is not only due to the macroeconomic situation (war in Ukraine, recession, etc..). Between July and September 2022, almost 30 percent fewer new companies with innovative and technology-focused business models were registered than in the same period of the previous year.

What is going on? It is not a secret that Europe’s research organizations have been less effective than that of the US at turning start-ups into late-stage successes. Maybe it is simply a lack of proper business education of EU researchers? Fact is that European start-ups have consistently lower success rates and show less progress through all series rounds when compared to US and Asian start-ups the EU droppin billions of Euros into its research organizations every year. It seems obvious that research bodies need to provide more support to their talents. Overall, at Parallel Space we have identified three areas where young academic entrepreneurs can be supported, to fight the tendency of EU research organizations to neglect efforts to commercialize their technology:

The first area where researchers need help is in the idea stage.

At this early stage, access to an outsider’s opinion, even for a few hours, focused on a specific challenge researchers are struggling with, can make all the difference.

Case Study 1:

I remember, many years ago, when I was a young group leader, running a lab at the Klinikum rechts der Isar in Munich, I developed a new protocol for isothermal PCR. Just by adding a couple of ingredients to the PCR mix, it could increase the yield to comparable protocols by a factor of 100, making single-cell analytics much easier. I knew it was worth making a kit out of it and hence I talked to a leading company that “delivers Sample to Insight solutions for molecular testing” to laboratories. While there was a definite interest from the company in my method, I had no idea how to make a deal with them. How do I go about telling them what the method is all about without giving them the secret sauce of the protocol? How much to ask for it? Licence or sell? Would an NDA make sense? Because my contact person went on vacation and I was super busy with my lab work, I just forgot about it – and the valuable IP that I developed in the lab was just forgotten and buried in my old lab books.

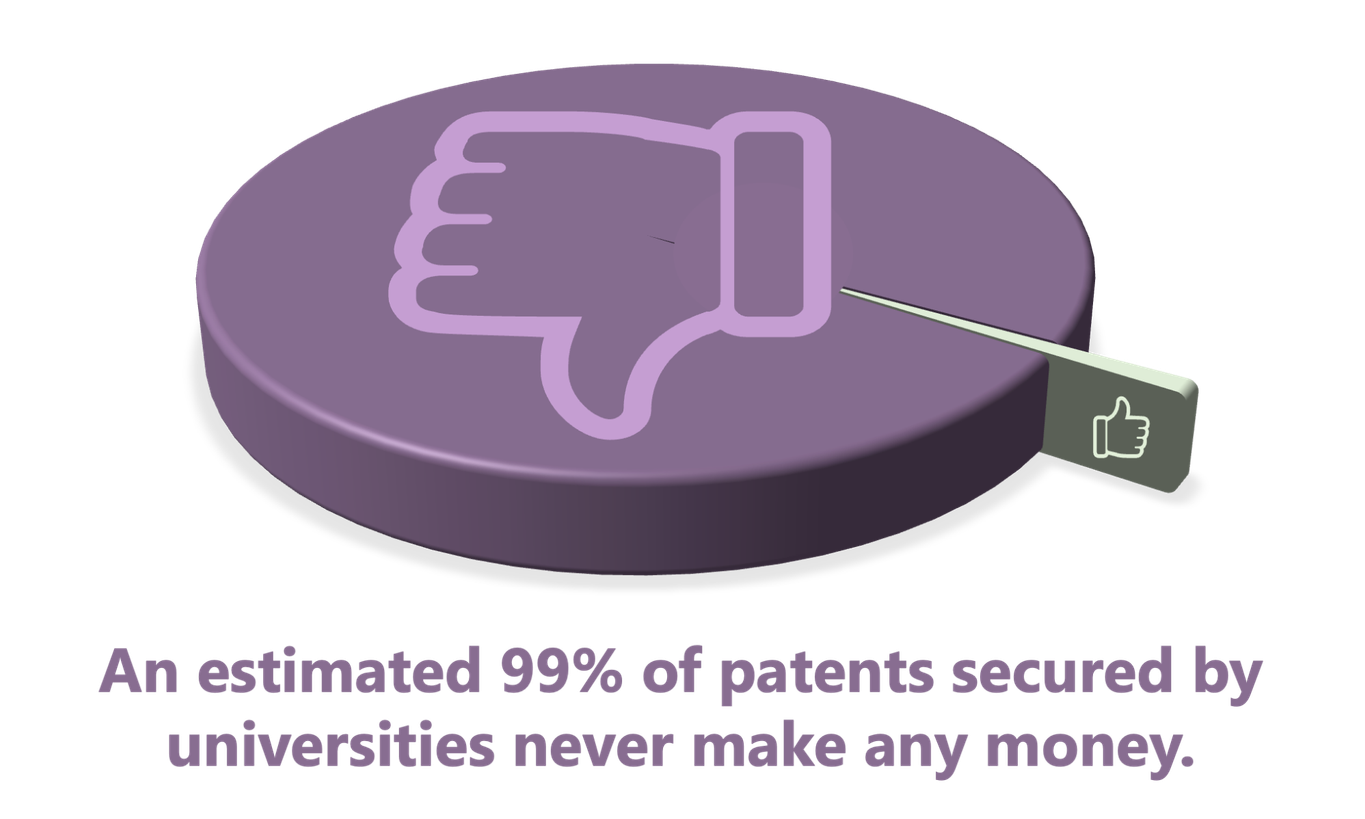

This example exemplifies that not every new discovery merits starting a spin-off, often the value is in much smaller things. While some universities provide dedicated support for patents and technology transfer (e.g., via a technology transfer office), they miss many chances of monetizing other parts of their research output. After all, research is expensive, and there should be a means to recoup at least part of the cost; nothing wrong with that. The problem with patents is, they are very expensive and cost time! Research institutes often miss the point that entrepreneurship means time to market and approaching the venture from a solid business standpoint. Filing a patent is not entrepreneurship. In fact, studies show that most research universities lose money on patenting and licensing technologies.

Looking back, as a young researcher I had not the time nor the skills to monetize my discovery. If I had the help of people outside the lab who could have taken my protocol and helped me monetized it; that would have been a game changer. There are many ways where research organizations could help, for example, supporting open IP, hiring business managers that monetize smaller inventions, sharing fractional IP via ‘smart contracts’, or giving out the IP to an outside venture that handles all the monetization efforts which then share revenue with the university and researchers.

The next area where researchers need help is during the early phases of the start-up/spin-off.

While researcher-led spin-offs in European countries are not necessarily more prone to failure compared to US start-ups; it cannot be denied that European tech start-ups are more likely to stall after a fundraising round, meaning they simply don’t advance to the next stage of funding or don’t manage a successful exit (IPO/acquisition).

Case Study 2:

When I was a young postdoc, I developed the so-called epigenetic microarrays, making it finally possible to interrogate the whole genome for epigenetic patterns; opening new ways for pharma companies to add epigenetics to their R&D portfolio. In the lab, we discussed if there is a way to monetize the invention as we knew it had massive potential. But how? None of us had ever started a company. How to get money to make a product out of it? How to protect the IP? How to even find the time to start a venture, keeping in mind that we worked 100-hour weeks? We had no guidance whatsoever; the only thing we had was that the institute helped us to write a patent application. In the end, we didn’t start a company, instead we patented the invention and licensed it to a German biotech company for a 6-digit Euro amount. Was it a good deal? The biotech used the technology to develop their main drug target, making millions of Euros in the process. Did we get rich? Well, 25% of the revenue was taken by the institute, another 25% by the department, and yet another 25% by my boss. After spending months on the patent, paying for the patent lawyers and taxes, from the previously nice-looking licence fee, all that was left in my pocket were less than 300 Euros.

Often, it is helpful to engage a dedicated start-up coach for the research team during those early stages, when the venture is not yet matured and many insecurities about the path ahead exist. Universities should be open to engaging external advisors for start-ups. Of course, this should not be some theoretical advice or a course/workshop in entrepreneurship. Instead, almost all start-up teams need a dedicated, experienced entrepreneur (or a team of entrepreneurs with different expertise) who will enjoy working with them for several weeks or months, even years, to address their specific challenges. Researchers will learn most by working with experts, outperforming any theoretical advice any time. When all else fails, mostly due to the lack of enough time for busy researchers, they should have the option of hiring a part-time interim CEO (ideally funded by the research organization) to see the start-up through the next phases. An experienced executive may help de-clutter their stalling business model and bring them back on track.

The final area we want to discuss is the university ecosystem as such; this is what we call the start-up habitat.

Remember, most research bodies, particularly universities, occupy an important space at the intersection between science, innovation, business, and public policy. Unfortunately, many organizations do not leverage their position in the innovation ecosystem. University- or non-profit-led incubators need to become more modern, linking all of the verticals they occupy, and directing them toward adding value to the university’s start-ups; anchoring the organization in the public image as a force for real-world impact. Universities must adopt entrepreneurial thinking. Entrepreneurship needs to be their product and each product needs a suitable marketing to get it into the market, leveraging podcasts, YouTube channels, Demo days, Mobile-platforms, Life-Events…, and so on. At present, most synergies lie dormant, and start-up platforms or ‘venture labs’ are not fully formed.

“Working in science meant publish or perish. Any time taken from research for other activities would have meant hurting our publication record.”

But most importantly, a start-up habitat needs hand-on expertise from entrepreneurs (ideally also former researchers) who went through the process already: Usually, only few people at the research institutes or tech-transfer offices have ever launched a company. But researchers do not need theoretical advice from an MBA, they need advice on small real-world problems. How to set up an CRM system, how to find data for a competitor analysis, how to find affordable developers, how to reach out to partners in India, how to form an advisory board, how to structure development of an MVP, what to include into a roadmap, how to prepare the pitch deck and how to present it to the investors etc…

In the end, our busy researchers need mentors, managers, and people who do things that a student, postdoc or professor has no time for. Scientists require networks that the universities can provide. Researchers need lab space, data infrastructures, government contacts, computing power, alumni networks, (impact) investor collaborations from the idea stage, in-house interdisciplinary networks (e.g., the AI department talks to the lung cancer department), and a bridge to the industry. Finally, universities should guide their entrepreneurs towards spinning off impactful products and services oriented towards meeting the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development goals, as that is what society urgently needs.

Conclusion: European research organizations have almost all the necessary elements to allow tech spin-offs to grow and scale. More research organizations should learn from their US or Asian counterparts, be innovative and modern, and look at how to support their scientists to further grow their start-up ecosystems.